Automated PFAS analysis opens window to hidden sources

Researchers are uncovering previously unknown sources of PFAS using robotic sample preparation and high-resolution mass spectrometry

4 Dec 2025

Lee Ferguson, professor of environmental engineering and environmental chemistry at Duke University

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) have been raising concern across environmental science and public policy for decades. Their resistance to heat, water, and chemical degradation makes them useful in everything from firefighting foams to non-stick cookware and food packaging. But those same prized properties also make PFAS exceptionally problematic. Once released, these ‘forever chemicals’ can persist for decades, readily move through soil and groundwater, and bioaccumulate in wildlife and people. Most concerningly, several PFAS compounds are reprotoxic and potentially carcinogenic.

Despite years of research, the full extent of PFAS contamination is still emerging. Lee Ferguson, a professor of environmental engineering and environmental chemistry at Duke University, is among the researchers working to understand just how far the PFAS problem goes.

“The mission is to really understand the scope, exposure, transport, and fate of PFAS,” he says. “We’re particularly focused on identifying and tracking PFAS from novel sources, trying to uncover understudied or relatively unknown uses and releases of PFAS.”

From textiles to clean energy

That focus has led Ferguson’s team to two underexplored contributors: textile production and, perhaps more surprisingly, clean-energy technologies.

In their latest study, Ferguson and his team identified a previously unrecognized form of PFAS contamination in textile manufacturing. “We discovered that textile manufacturing is using nanoparticle-sized PFAS polymers, side-chain fluorinated polymers, which are released into the textile waste streams and get into the wastewater treatment plants,” he explains. “They're completely invisible to most PFAS analytical methods because they're too high molecular weight – they're actual colloids and nanoparticles.”

To detect them, the team had to develop new methods to convert these particles into measurable PFAS. “To our knowledge, this is the very first report of these colloidal nanoparticulate PFAS being a pollution hazard in textile waste,” Ferguson says.

The group is also investigating PFAS connected to the clean-energy transition, particularly in lithium-ion batteries. Energy-storage systems are crucial to renewable energy strategies, but Ferguson notes that the environmental behavior of key battery materials, including fluoropolymers and electrolytes, remains poorly understood.

To address this, the team has been testing the leachability of battery components and analyzing samples near manufacturing and disposal sites. Their findings, recently published in Nature Communications, reveal that lithium-ion battery production and waste streams represent an emerging and previously unrecognized source of PFAS release.

In particular, the team detected bis-(perfluoroalkylsulfonyl)imides (bis-FASIs), a class of fluorinated compounds used in battery electrolytes, at environmental concentrations comparable to those of regulated PFAS such as PFOA near battery-related facilities. The work suggests that without proper oversight, the clean-energy transition could inadvertently contribute to a new wave of persistent organic pollutant emissions.

A walkaway workflow for PFAS analysis

Identifying and quantifying PFAS for this research is no easy task. One challenge is the vanishingly small concentrations at which these chemicals matter. “The concentrations at which PFAS are relevant to the environment are in the part per trillion range, sometimes lower,” explains Ferguson. “At the same time, you’re dealing with thousands of potential compounds in very complex matrices, which places significant requirements on the analytical methods and instrumentation we use.”

Mass spectrometry is the mainstay for PFAS detection, and Ferguson’s team relies heavily on high- and ultra-high-resolution MS-MS, paired with sample-preparation workflows capable of extracting PFAS from notoriously messy matrices, including lithium-ion battery leachates.

Sample preparation, he says, is where the biggest bottleneck lies. “Previously, we've relied very much on manual, very time-consuming sample preparation to isolate PFAS from complex environmental as well as biological samples,” he explains. “The problem with those methods, whilst they've been validated with US EPA standards, is that they're extremely time-consuming, prone to contamination, and take an expert, so really limit your throughput and ties up expert hands.”

To tackle this bottleneck, the group has been working with CTC Analytics and Thermo Fisher Scientific to automate the key extraction and cleanup steps, including weak anion exchange and graphitized carbon methods that have become standard for PFAS analysis.

“We’ve been trying to package all of that into a robotically assisted, fully automated sample-preparation system that can process many samples, either simultaneously or sequentially, while interfacing directly with the mass spectrometer,” Ferguson says. “It’s a completely hands-off workflow that still meets the stringent procedural requirements of methods like the EPA’s 1633, which many US laboratories are required to follow.”

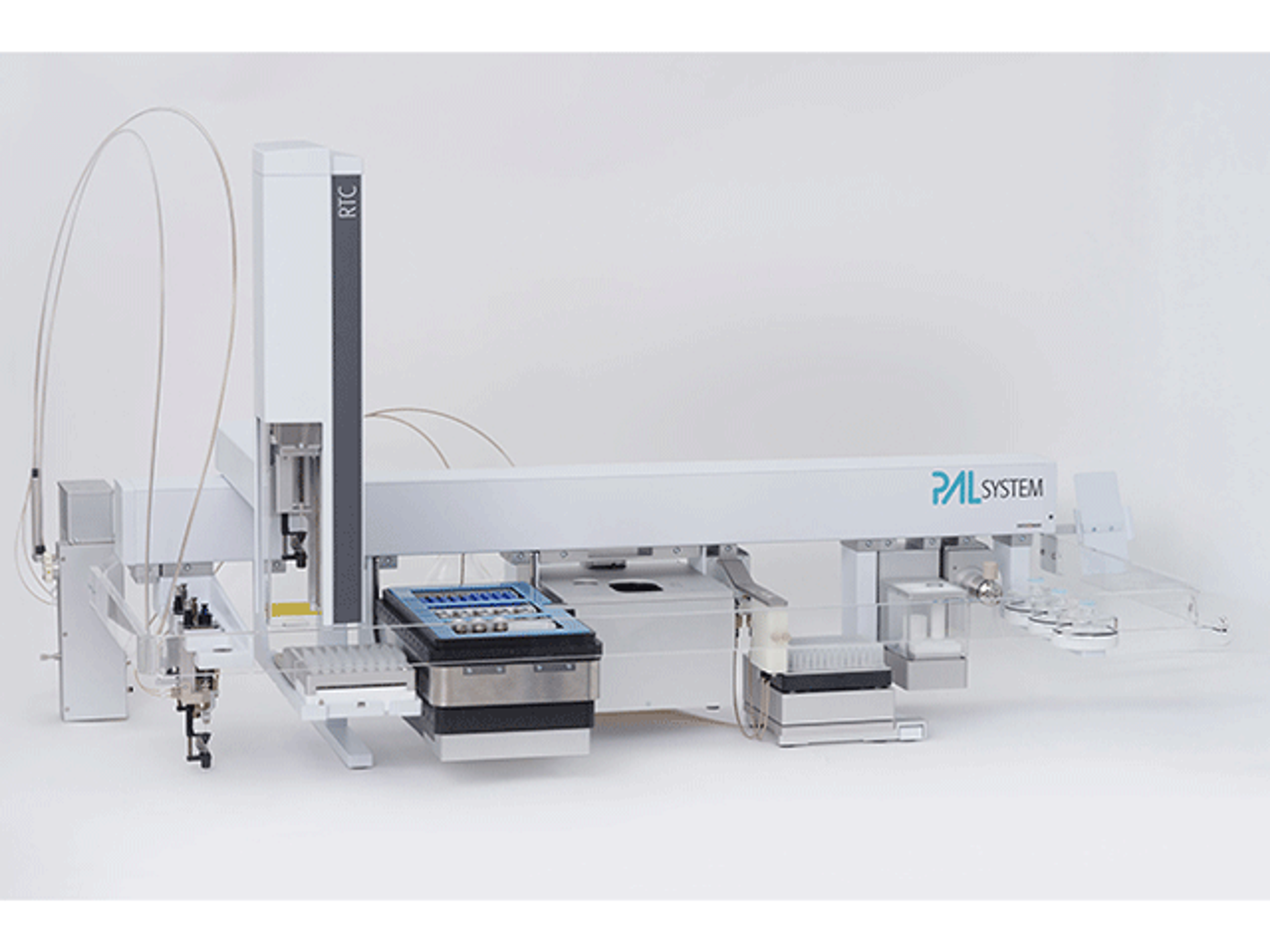

At the core of the setup are CTC PAL Systems. “We’ve pretty much standardized on the PAL platforms, and there are many reasons for that,” Ferguson says. “The quality and support are top-notch, and the systems are incredibly flexible, which means we can design a sample-prep workbench that’s not only highly adaptable but also extremely capable.”

“All of the modules are supported by PAL System and we can mix and match these to suit our specific analytical goals,” he continues. “That makes method development much easier, and we can then deploy those methods directly with the high-resolution mass spectrometers, as well as our conventional triple quadrupole mass specs.”

Higher throughput and fewer errors

The PAL System enables fully automated online sample preparation and injection for a wide range of PFAS analysis workflows

In the hands of Ferguson and his team, this setup has been a “game-changer”. Using the manual EPA 1633 workflow, his team could typically process only 6 to 12 samples a day. “Now, the same preparation takes just 20 to 30 minutes per sample,” he says. “It runs automatically, 24 hours a day, so our throughput has increased enormously.”

Because the PAL robots are directly connected to the mass spectrometers, the entire process is hands-off. “All we do is take the raw sample — wastewater, landfill leachate, surface water — load it into the system, and the workflow carries it all the way from field sample to data collection with no user intervention,” he enthuses.

While the throughput boost was expected, one of the more surprising advantages has been contamination control. “Normally, every few weeks we’d run into some sort of blank contamination from sample handling or something in the lab like a new reagent,” Ferguson says. “Having all these sample prep steps automated with our PAL System allows us to keep really tight control of that contamination, and it's brought our blanks way down.”

Help from CTC

Collaboration with CTC Analytics has been essential to this success. “In our case, because we weren’t using prepackaged workflows and were developing them from scratch, we really needed constant contact and support from the CTC team, all the way from the R&D engineers to the sales support,” Ferguson says.

That support included extensive training. “We've had training on everything from the hardware, where we've had on-site technicians and scientists from CTC in the laboratory helping us to configure the systems themselves, all the way to very intensive software training with the CTC factory on actually writing scripts and designing new workflows,” he explains. “That really allowed us to understand the advantages, as well as what the limitations are, on these systems, and then make maximum use of them.”

Advice for other researchers – and looking ahead

For researchers entering or expanding their work in PFAS analysis, Ferguson strongly encourages exploring automated sample-preparation systems for both GC-MS and LC-MS. “Even though it's a significant investment up front, it'll really pay dividends in productivity, throughput, and the quality of the data,” he says.

He also acknowledges a shift in the industry from triple-quadrupole to high-resolution mass spectrometers, not just for non-targeted analysis, but also for sensitive and selective quantitative analysis. “I would really encourage scientists who are moving in this direction to consider having a high-resolution mass spectrometer, because the sensitivity is almost as good as the triple quads in some cases, but also, due to the fact that you're getting some non-targeted high-resolution data, you can revisit archived samples for retrospective analysis,” he says.

Looking ahead, several analytical gaps still need to be addressed in the field. Volatile and semi-volatile PFAS remain a particular challenge. “One big area is to try to come up with better ways to do soft ionization on GC-separated PFAS, so that we can preserve molecular ions, and follow the classical paradigm of molecular ion to fragmentation to structure that we do for non-targeted analysis in LC-MS-based workflows,” Ferguson explains.

Then there are PFAS outside the reach of current methods, such as the colloidal nanoparticles his team discovered in textile waste. “We just don't have any good analytical methods to detect those and quantify them,” he says. “So, we really need to push that forward,” he concludes.