Management by walking around (MBWA) in the clinical laboratory

Guest editorial by Susan Dawson, Consultant, Speaker, Writer at Accomplish More Consulting Services (AMCS)

18 Dec 2024

Susan Dawson is a recently retired Laboratory Director with over 40 years of experience. She is the founder of Accomplish More Consulting Services (AMCS)

Like many in the lab science field, I started my professional career not having any business or leadership classes in high school or college. I was solely committed to a science and math curriculum, and though I attended a liberal arts college and took many classes that expanded my knowledge base and challenged my thinking, no business classes were required. I had no interest in taking one either.

My career path in laboratory science took me on a fast track to supervisory and management responsibilities. I found myself learning business lingo and financial strategy on the job but it was clear I needed to get an educational foundation in business management. An MBA program was offered to me and I immediately accepted the offer. With no previous business classes, I was required to take remedial courses in accounting, both cost and financial, to qualify to enter the MBA program.

My science-wired brain was challenged to bend in new directions to understand the complexities of management, marketing, accounting, business statistical modeling, conflict management, and operational efficiency. My effectiveness as a leader and a strong understanding of business operations, combined with the technical knowledge, clearly proved to be beneficial when calculating ROIs for new instrumentation and methods, and setting forth budget projections for 3-5 years. Classes in operational management, effective communications and problem solving provided additional key elements and actionable information. I really thought I was all set!

Management by Walking Around – MBWA

Soon after completing my MBA, my director challenged me to start working on my MBWA. My MBWA? I was totally confused. He quickly defined it – Management by Walking Around – MBWA. I could have all the book knowledge in the world, but I needed to put learning into action and develop a relational presence with my staff. This wasn’t a class taught in school. Where was I to begin?

I had never really noticed it before, but then I started watching him, and each day, he would begin his work day by walking around and “checking in” with everyone. The interactions would be quick sometimes, and other times take 5-10 minutes, but he was connecting with the supervisors, managers and front-line staff, building relationships and eventually trust at every level. There was one supervisor who would clearly talk his ear off almost every day. She had a kind of irritating voice, and would talk unnecessarily loud at times, but he would patiently listen to her, acknowledge her and treat her as if she was the most important person in the world. Most of the time, whatever she was telling him, in quite specific detail, with her own commentary filling in as necessary, was probably not unknown to him. I asked him how he could endure hearing this rehash of what he already knew and yet patiently listen. His response was that, sometimes, and you never knew when, there would be a “golden nugget” of information that he could glean and use, or that he needed to be aware of, and for those times when this happened, listening for 10 minutes every day was worth it!

I can’t tell you the number of times he came to me or one of the supervisors and provided information about an issue that had happened last night or a problem that currently existed in the department that we were unaware of or that was not yet resolved. They were stunned. I was stunned sometimes too. The staff had shared something with him, a director, but hadn’t said a word to me, the manager. I clearly understood the value of the conversations and relationships he had developed with the staff. Through his MBWA, the lab worked better due to the knowledge sharing, communicating and the acknowledging of their work that was happening on a daily basis.

I started to think about what I wanted people to know and how I wanted people to feel about interacting with me. If I wanted to be an effective communicator and leader, I needed to put into practice my own style of MBWA. The practice of MBWA did not need a master’s degree. It required legs to walk around, and ears to listen. I needed to define my own leadership style for my staff. I couldn’t become the same type of person or do the exact same thing as this director was doing. He had set his pattern and his style, and everyone knew and expected him to be making his daily rounds and engaging them. It would be redundant for me to be doing the same. My style and approach needed to be something that was comfortable for me.

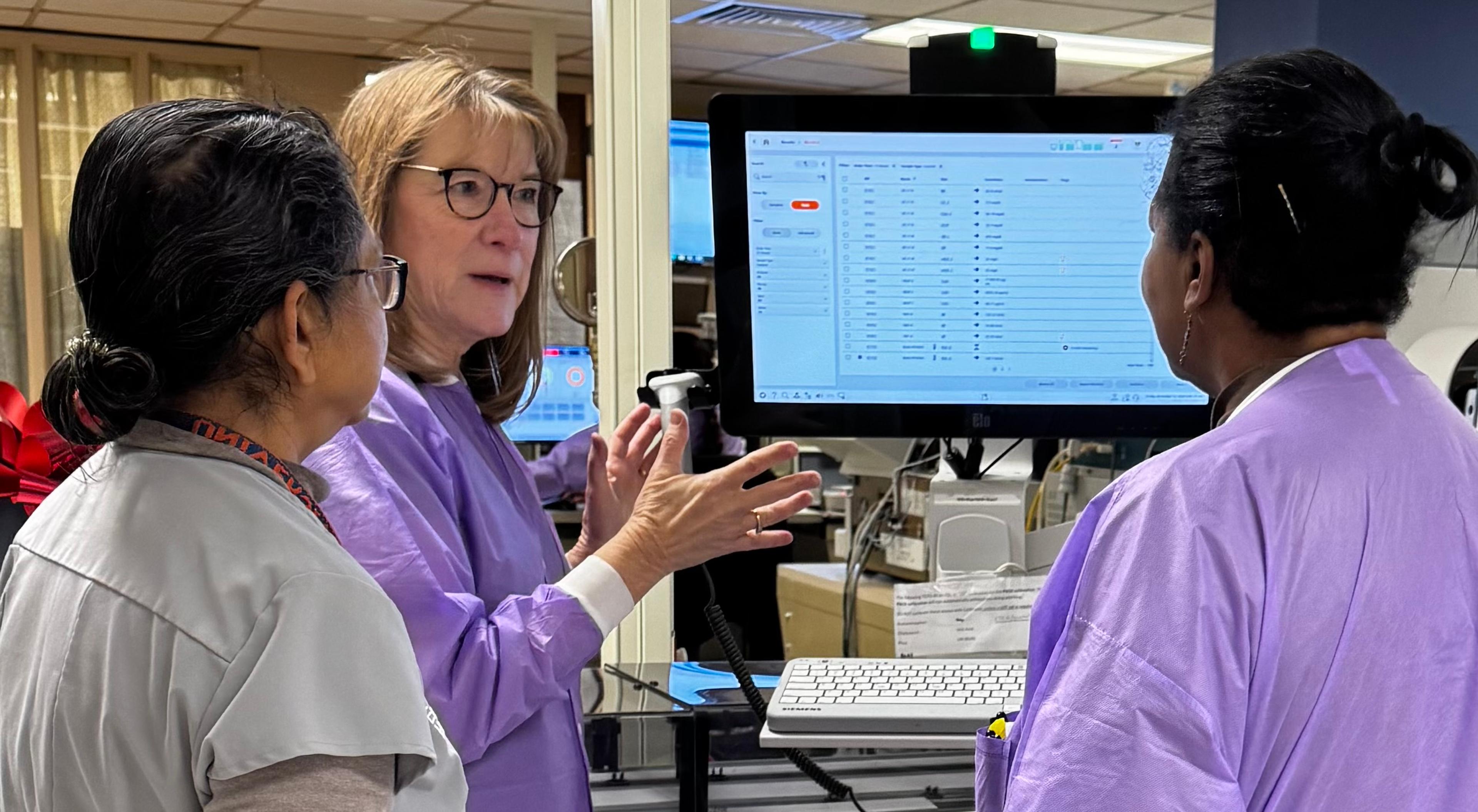

Many of my management responsibilities involved being in the laboratory, taking care of operational workflow or managerial tasks or responsibilities, attending to problems with instruments, and training staff. While I was doing these things, I began engaging my team in conversation and thinking about what it was like when I was in their place through personal conversations and sharing. It became clear to me what I wanted to do.

I started to work on meeting their unspoken needs, reducing their stress, making processes more efficient and working quietly to help them. For example, when things got busy, I didn’t intercede or interfere in what they were doing, or bump them out of the work assignment they had and take over because I could do it faster or better. Instead, I started coming in behind them, so to speak; I had their back. I took on the tasks that needed to get done but that they didn’t have time to do. For a portion of many days, I was probably the highest paid stock boy or stock girl in the hospital. I would put away supply orders when they arrived. I would walk to the Urinalysis bench to start processing specimens and loading them on the instrument. I would clean up after someone or relieve them so they could move on to complete analyzing samples. There was no job or task that was beneath me. I put myself in a position to serve them.

At the same time, I wanted to change the culture, the interactions, and the tone of the lab, and through this process, I wanted to learn about them and what made them who they were, what was important to them, what they enjoyed, what brought meaning to their life. In this process, they shared many things with me including cultural norms and traditions. I didn’t sneak around behind them or double-check their work. They could clearly see that I wasn’t there to spy on them, catch errors, or snoop around for problems. I wanted them to know that I cared about them as people, not just as employees.

My ultimate goal was to make sure that at the end of the shift, every employee had enough energy for their life outside of work – whether it was family and friends or hobbies and passions.

Serve first, lead second!

I took on the role of “a participative leader” and this organically became my style of MBWA. It was not just Management by Walking Around but was Management by Working Alongside. I was not directing, providing instruction, or managing at these times. Instead, I was doing the bench work, pitching in and helping the staff wherever I could. I washed pipettes and glassware, switched out garbage cans that were full and cleaned counters. As a further commitment to being this type of leader, when I wasn’t walking around the lab, my office door was open 90% of the time, and they knew that if they needed help, there was nothing that I wouldn’t do to help them, just let me know and I will be there.

As my MBWA style developed, it also involved filling holes in the schedule, including holes on the PM shift and the night shift. The first few times I showed up to work the PM or night shift, the reaction of the staff was one of surprise and suspicion! But they soon learned that I was there to work and help them. The appreciation that we mutually shared for each other, and the dedication we had to the work and the work that we accomplished together could not be understated. I walked a mile in someone else’s shoes. I discovered problems and learned first-hand of the challenges from the perspective of staff working the second and third shifts and subsequently incorporated those learnings and that information into future decisions that were made that would affect all shifts.

It has often been stated that the workplace takes on the personality of the leadership, and I have found this to be true. The communication style practiced by the director allowed for open, honest communication and a caring attitude among the staff. My example of participative leadership led to an environment of mutual commitment and willingness to go the extra mile, work the extra shift, and pitch in to help your coworker without being asked.

You need to model the behavior that you want people to adopt.

As John Wooden, the famous and highly successful UCLA Basketball coach said, “The most powerful leadership tool you have is your own personal example.”

Today, the laboratory field is challenged with everything from budget constraints to change management to staffing shortages and staff burnout. People who enter the field of laboratory science do so because they see an opportunity to use their skills and interest in science to serve the healthcare field in a significant way. Laboratory leaders need to juggle many challenges. Those who can be supportive, create solutions to problems, help optimize workflow, and understand the challenges faced daily by their staff will not only help retain employees but will provide an environment that produces a high-quality product and employees who feel appreciated and valued.

Susan Dawson is a recently retired Laboratory Director with over 40 years of experience. She is the founder of Accomplish More Consulting Services (AMCS). This story is from her first book, Growing Into Leadership: Lessons Learned Along the Way" available through Amazon and Barnes and Noble online.