New Guidance for Physicians for Accurately Diagnosing C. Difficile Infection

Screening for C. Difficile will reduce number of avoidable deaths, writes guest editor Gosia Leitch, Global Product Director with Alere

18 Sept 2017

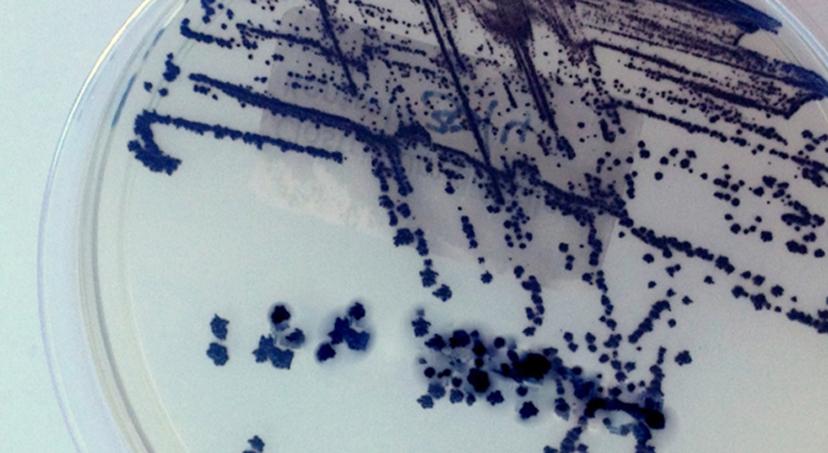

Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) is a potentially fatal bacterial infection that causes inflammation of the colon and leads to 3,700 deaths a year in Europe.1 C. difficile infection is highly symptomatic, causing abdominal cramping, diarrhea, fever, mucus or blood in stool, and elevated white blood cell levels. Despite these pronounced and serious symptoms, patients often are not tested for C. difficile. In fact, almost two-thirds of CDI cases are missed because clinicians fail to request tests for C. difficile toxins in cases of unexplained diarrhea, underscoring that much more must be done to stop the spread of this dangerous infection.2

There are various systemic reasons for the underscreening of CDI. Half of all European hospitals screen for CDI only at the request of the physician.3 Diagnostic strategies that involve testing only upon physician request underestimate the prevalence of C. difficile.4 A recent study showed that 82 patients with CDI were not diagnosed across Europe on a single day; this equates to more than 39,000 missed diagnoses each year across the continent.5 Moreover, more than half of hospitals still do not use the most accurate testing procedure for CDI and more than one in five samples found to be positive for CDI by study investigators had not been tested at the local hospital level.6

Join our free online webinar: 'Diagnosis and Prevention of Clostridium Difficile Infection'

When CDI remains undiagnosed and untreated, it not only endangers patients’ health, it also poses a serious cost to healthcare systems. In Europe, the potential cost of CDI is estimated to be €3 billion for each year — and is expected to almost double over the next four decades.7 CDI has an enormous impact on healthcare systems as infected patients are often hospitalized an extra one to three weeks at an additional cost of up to €14,000, compared with patients without CDI.8 As the incidence and severity of CDI continues to increase, it is essential that CDI testing practices in hospitals improve.

Leading medical organizations are starting to address this lack of screening with new guidelines. For example, the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) recently made important updates to their guidelines on diagnosis of CDI.9 Among them, the guidelines include a new recommendation for empiric testing of all unformed stool samples for patients over three years old. ESCMID also recommends that a follow-up Toxin A/B test be used to validate a positive result from a molecular test for optimal specificity and sensitivity of results. Fortunately, there exist rapid tests today that integrate both components so that healthcare professionals can accurately diagnose CDI and immediately administer appropriate treatment.

Other regions that face challenges with diagnosis of CDI are beginning to adopt this testing protocol. In the United States, where the majority of hospitals use molecular tests to diagnose CDI, often as stand-alone tests, there is a movement towards adopting ESCMID’s guidelines. CDI is linked to about 30,000 deaths a year in the United States — about twice federal estimates and rivaling the 32,000 killed in traffic accidents.10 Hospitals in the U.S. and other countries should look to these guidelines as a roadmap to help control the spread of CDI and stop the avoidable deaths caused by this dangerous infection.

References:

- 1 European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Clostridium difficile infections. Accessed on December 5, 2016.

- 2 Oake N, et al. The effect of hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile infection on in-hospital mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1804-10.

- 3 UK Health Protection Agency. English national point prevalence survey on healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial use, 2011: preliminary data. London; Health Protection Agency, 2012

- 4 Hensgens MP, et al. All-Cause and disease-specific mortality in hospitalized patients with Clostridium difficile infection: a Multicenter Cohort Study. Clin Infect

- 5 Lowy I, et al. Treatment with Monoclonal Antibodies against Clostridiumdifficile Toxins. N Engl J Med. 2010;362;3:197-205.

- 6 Bouza E, et al. Results of a phase III trial comparing tolevamer, vancomycinand metronidazole in patients with Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea. Clin Micro Infect. 2008;14(Suppl 7):S103-4.

- 7 E. J. Kuijper et al. Emergence of Clostridium Difficile-Associated Disease in North America and Europe. Clinical Microbiology and Infection: The Official Publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 12 Suppl 6 (October 2006): 2–18, doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01580.

- 8 Magalini S, et al. An economic evaluation of Clostridium difficile infection management in an Italian hospital environment. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16:2136–41.

- 9 M.J.T. Crobach, T. Planche, C. Eckert, F. Barbut, E.M. Terveer, O.M. Dekkers, M.H. Wilcox, E.J. Kuijper. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID): update of the diagnostic guidance document for Clostridium difficile infection (CDI). Clin Microbiol Infect 2016

- 10 Eisier, P. USA Today, “Far more could be done to stop the deadly bacteria C. diff”. August 2012. Accessed: 08 Feb 2016